A powerful geomagnetic storm is affecting the planet from November 12–14, raising questions worldwide about space weather and its potential risks. Indonesia’s meteorological agency, BMKG, has assured that the country faces minimal impact, yet the event offers a moment to understand why this type of solar disturbance matters.

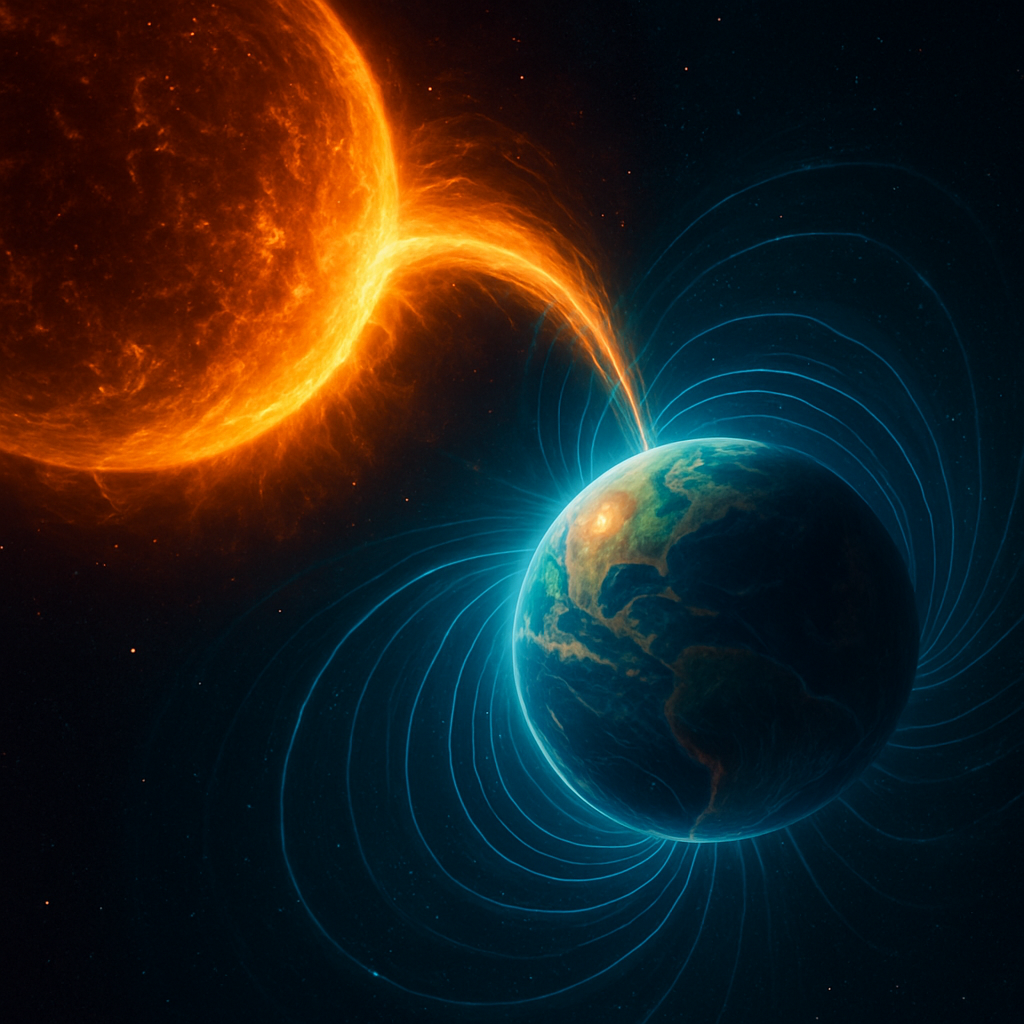

A geomagnetic storm occurs when the Sun releases massive bursts of plasma and magnetic fields — known as Coronal Mass Ejections — that collide with Earth’s magnetosphere. These storms vary in strength, but the more severe ones have the potential to interrupt satellite signals, disrupt radio communications, and in extreme cases damage electricity infrastructure. Scientists often cite historic events as reminders of what a worst-case scenario might look like.

One of the clearest examples is the Carrington Event of 1859, still considered the most intense geomagnetic storm ever recorded. It took place on September 1–2, producing auroras visible around the globe and causing telegraph equipment to spark and overheat. The bright solar flare linked to the event was independently observed by British astronomers Richard Carrington and Richard Hodgson — the first recorded observation of a solar flare. Experts warn that an event of this scale today could severely disrupt electrical grids and communication systems across multiple continents.

Indonesia’s position in the current geomagnetic storm

BMKG confirmed that the storm now underway was triggered by an X5.1-class solar flare — one of the stronger categories observed in space weather monitoring — and reached a G4 level on the NOAA scale, indicating severe activity. Despite this, Indonesia’s equatorial position provides natural protection. According to BMKG’s Syirojudin, the Equatorial Electrojet acts as a shield that weakens the flow of high-energy particles toward the region.

Monitoring stations in Tondano, Tuntungan, and Serang recorded a high K index beginning on November 12, with elevated activity expected through November 14. Even under these severe global conditions, Indonesia is forecast to experience only minor to moderate disturbances. These may include brief disruptions to GPS navigation, satellite communication, and high-frequency radio — key systems for aviation and maritime sectors.

Why the global risk matters

Experts note that long power transmission lines in places like North America, China, and Australia are the most vulnerable during a geomagnetic storm, as induced electrical currents can overload transformers. Historical research, including studies on the 1921 storm, suggests that extreme events could destroy hundreds of transformers in some regions. While U.S. regulators have since introduced stricter testing and protection rules, the broad scientific consensus remains: a major geomagnetic event today would strain modern electrical and communication systems in ways the world has never experienced.

Indonesia’s grid, however, is less exposed. The country’s geography places it outside the highest-risk zones, and BMKG stresses that local infrastructure should remain stable. The agency nevertheless recommends that operators in aviation and maritime transport maintain backup communication procedures and monitor magnetospheric activity using K and A indices.

For now, the message from BMKG is reassuring: Indonesia’s daily life and power systems remain safe, but staying informed is still the smartest approach during a geomagnetic storm of this scale.